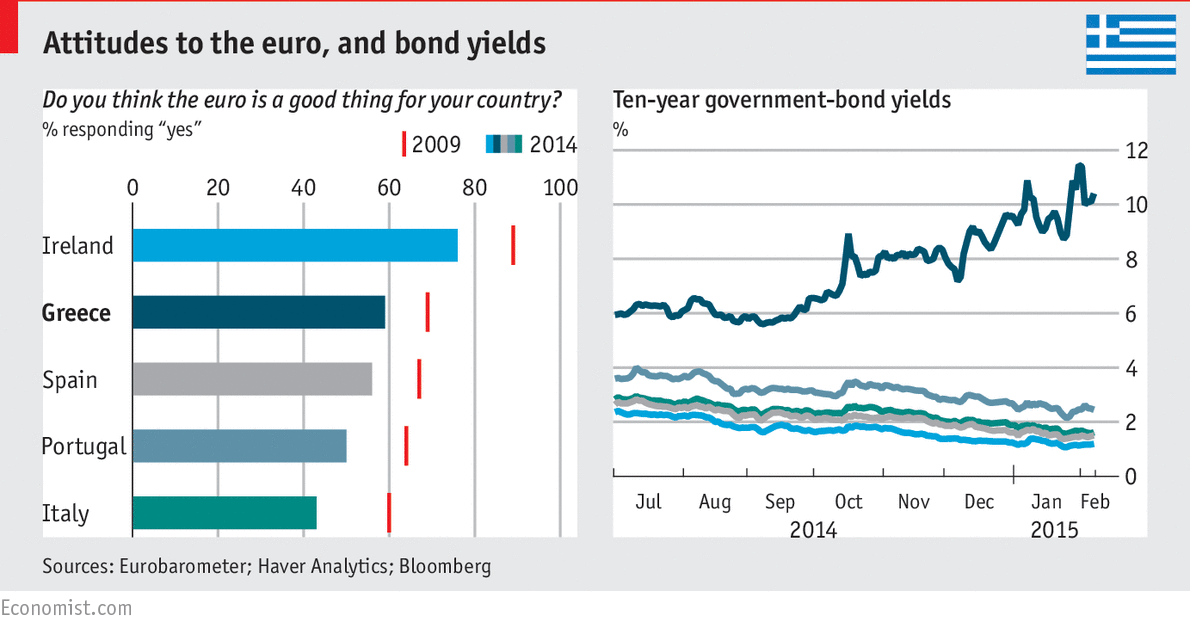

GREEK voters want to stay in the euro. They have also elected a government that has made a Greek exit, or "Grexit", seem much more likely. Wolfgang Schäuble, Germany’s finance minister, said on February 10th that if Greece's new Syriza-led government did not seek an extension of its bail-out, which expires on February 28th, “Then it’s over.” A meeting on February 11th, at which Greece presented its plans to euro-zone finance ministers, ended in disarray, without even the usual statement about fruitful discussions. Unless some sort of agreement is found soon, another Greek default looms when IMF debts mature in March.

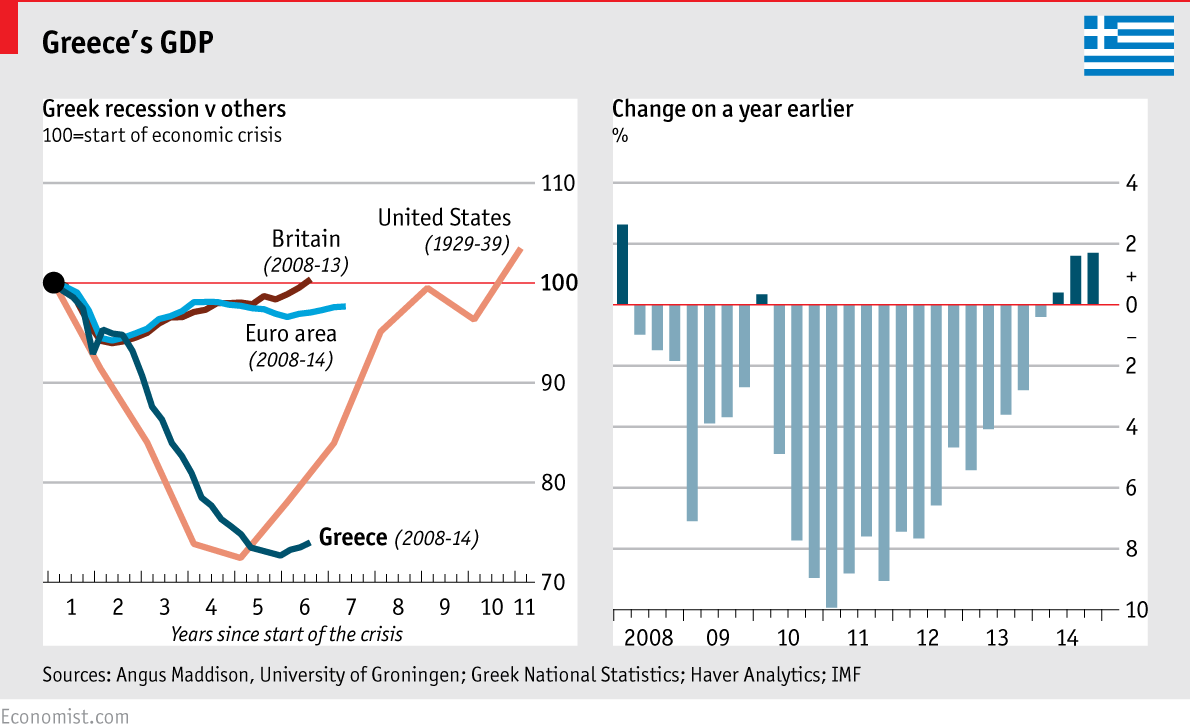

Political upheaval is already having an economic cost. Greece emerged from recession in early 2014, but its escape from contraction was short-lived. Figures released on February 13th showed the Greek economy still growing year on year, but shrinking on a quarterly basis in the final three months of 2014. Since 2008, the Greek economy has shrunk by about a quarter. Although not quite as deep a downturn as America’s Depression, Greece's recession was more prolonged and is likely to take more time fully to recover from. Recent downturns in the euro area and Britain seem like minor hiccups in comparison.

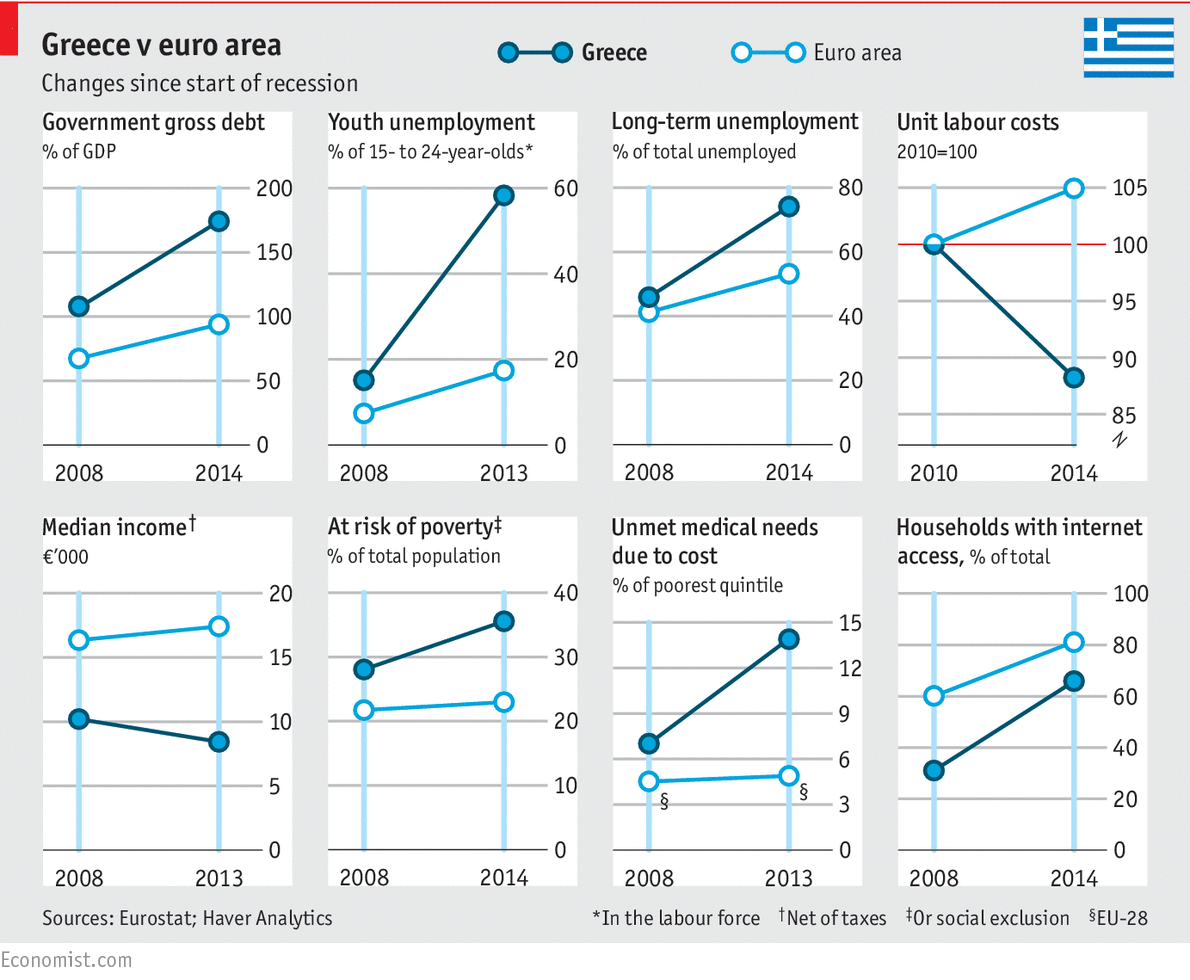

Having started to grow, Greece's economic recidivism is deeply frustrating. But Greek voters had plenty of reason to plump for change. Even before the crisis struck, Greece was a laggard. In 2008 only a third of households had the internet, the lowest share in Europe. Levels of youth unemployment and government debt were already among the continent's highest. Since then, the gap between Greece and the rest of the euro zone has grown. Unemployment has more than tripled to 26%, and three-quarters of the jobless have been out of work for 12 months or more. Over a third of Greeks are considered to be at risk of poverty, more than any other euro-zone member.

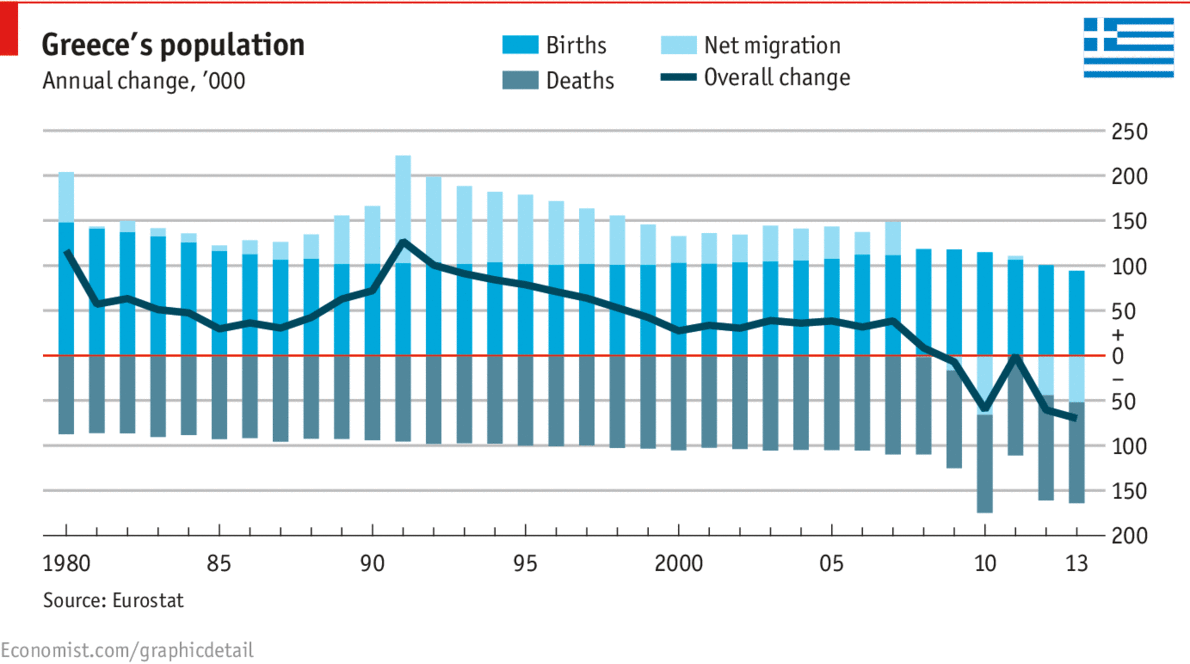

Worse still, the recession exacerbated some unfortunate demographic trends. Greece's population peaked in 2009 at just over 11m, because of falling fertility rates and work-hungry emigrants. This has pushed up Greece’s old-age dependency ratio (in essence, the ratio of people too old to work to those of working age), already one of the highest in the world.